About last night...

Last night's council meeting was objectionable.

It was supposed to be the first full meeting of a new City Council with a people-first agenda. But before the Council could even begin discussing several high-profile items, a procedural dispute brought the mechanics of City Hall — rather than the substance of policy — to the foreground.

Not So Fast... No, Really, Not So Fast.

At last night’s City Council meeting, five agenda items were halted instantly—before the public ever heard what they were.

As each item was called, Councilor DiBona objected immediately, before the City Clerk could complete reading the ordinance, order, or resolution into the record. Each time, the Clerk stopped reading. No discussion followed. No committee referral occurred. The Council moved on.

For residents watching the meeting, the result was simple: items came up, objections were shouted, and the public never heard what was being proposed.

That sequence of events is not disputed. What is disputed—and what deserves careful explanation—is whether this outcome was required by the rules, or whether it flowed from a misinterpretation of how those rules actually operate.

What Rule 23(B) Actually Does

Rule 23(B) is often described loosely as an “objection rule,” but its text is far more precise than that. It states that an ordinance, order, or resolution may be passed through all its stages of legislation at one session unless a member objects, in which case the measure is postponed for that meeting.

The key word here is “passed.”

Rule 23(B) is explicitly about final legislative action—voting a measure through all stages in a single session. It does not say that an objection stops the Clerk from reading the item. It does not say that an objection bars all other motions. And it does not say that an objection interrupts the normal flow of the meeting the moment it is voiced.

In short, Rule 23(B) is a brake on same-session passage, not a kill switch for the meeting itself.

Why the Public Should Have Heard the Items

Under the City Charter and the City Council Rules, the City Clerk’s role is ministerial and administrative: reading items, recording votes, and keeping the record. The Clerk does not control the floor, rule on objections, or determine sequencing. Those powers belong to the City Council President, subject to appeal to the Council.

An objection under Rule 23(B) does not become operative simply because a member calls it out. Like any parliamentary action, it has effect only when it is recognized by the presiding officer. Until then, the item remains before the Council.

Nothing in the rules requires the presiding officer to treat objections as interruptive. The Chair may allow the Clerk to complete the reading so the public knows what is being discussed. Doing so does not weaken the objection. It preserves transparency.

Why Referral Matters — and Why It Comes First

There is an additional, often overlooked point that makes this interpretation even stronger.

Under Robert’s Rules of Order—which govern where local rules are silent—a motion to commit or refer is a recognized procedural step that takes precedence over final passage of the main motion. Referral is not passage. It is the opposite: a deliberate delay for further consideration.

If the Chair allows a motion to refer an item to committee before recognizing an objection, several things happen:

The purpose of Rule 23(B) is satisfied. Once an item is referred, it cannot be passed through all its stages that night.

Order is maintained. The public hears the item, and the Council takes an orderly step to vet it.

The objection becomes secondary. Because same-session passage is no longer possible, the objection to same-session passage has effectively been honored.

Rule 23(B) does not say that objections override referral. It says they prevent passage. Referral already accomplishes that.

A Better, Lawful Sequence

Putting this together, a procedurally sound sequence could have looked like this:

The Clerk begins reading the item.

A member calls out “objection.”

The Chair states:

“A member has called out an objection. The Chair has not yet recognized it. The Clerk will complete the reading for the public record.”After the reading, the Chair asks whether there is a motion to refer the matter to committee.

If referral is moved and adopted, the item is sent to committee and cannot be passed that night.

Only if a motion for final passage is made does Rule 23(B) “fire,” requiring postponement due to the objection.

This approach fully respects minority rights while avoiding procedural silence.

What Was Objected To

It is also worth noting what these objections were directed at. Councilor DiBona objected to items concerning City Council compensation, including matters tied to recent raises, and to a motion intended to ensure the public has a regular, monthly opportunity to address the City Council.

These are not obscure procedural matters. They are issues on which the public has already expressed strong views through voting, public comment, and civic engagement. Whatever one’s position on the merits, these are topics residents reasonably expect to hear discussed openly.

By objecting before the items were even read, the practical effect was not defeat, but delay—asking the public to wait additional weeks to learn what was being proposed and why.

Parliamentary Rope-a-Dope

This episode illustrates a broader phenomenon I often describe as parliamentary rope-a-dope: using timing and procedure not to debate an idea on its merits, but to sidestep the process itself.

Such tactics may be technically permissible, but they are rarely popular. With few exceptions, the public does not view procedural delay as principled resistance. More often, it experiences it as a dismissal—not of political opponents, but of the audience watching from home.

People expect disagreement. What they react poorly to is being shut out of the conversation entirely.

The Takeaway

None of this requires speculation about motive. The facts are sufficient.

Rule 23(B) is a safeguard against rushed legislation, not a mechanism for cutting off public understanding. The rules do not require a race to object, nor do they require the Clerk to stop reading mid-sentence. Those outcomes result from choices about how the rules are applied.

Better governance—and better public trust—comes from using procedural protections as shields against haste, not as curtains drawn before the public can even see what is on the stage.

References:

Quincy’s City Council Rules

Robert’s Revised Rules of Order

But in the absence of information…

What made Councilor DiBona’s actions especially frustrating was the complete lack of any public explanation.

After the meeting wrapped up, reporters from The Patriot Ledger and The Quincy Sun approached Councilor DiBona to ask about what he’d just done. He was seen walking past them without acknowledging their questions. If there were a procedural reason, a policy disagreement, or even a principled stand behind the objections, that was a perfectly reasonable moment to say so.

There is no public evidence that these objections were coordinated with, directed by, or made at the request of anyone else. Nor would one expect the public record to contain evidence of private conversations unless someone chose to put them on the record. That’s simply how public records work. What the public can see, however, is what officials choose to say — and in this case, nothing was offered.

So people filled in the blanks. Some noticed that the objections delayed consideration of measures related to City Council compensation. Others saw it as a procedural shot across the bow at initiatives coming from a newly seated Council. Still others pointed to Councilor DiBona’s long tenure, and the relatively modest committee assignments he received this term, as possible context.

None of that can be confirmed without Councilor DiBona explaining himself. And that’s really the point. When elected officials use procedural tools in ways that stop the public from even hearing what’s on the table — and then decline to explain why — they shouldn’t be surprised when the public draws its own conclusions.

In local government, process matters because it’s how residents know they’re being taken seriously. When procedure is used to cut off information rather than slow down decision-making, it doesn’t come across as strategy. It comes across as dismissal. And silence, intentional or not, tends to make that worse, not better.

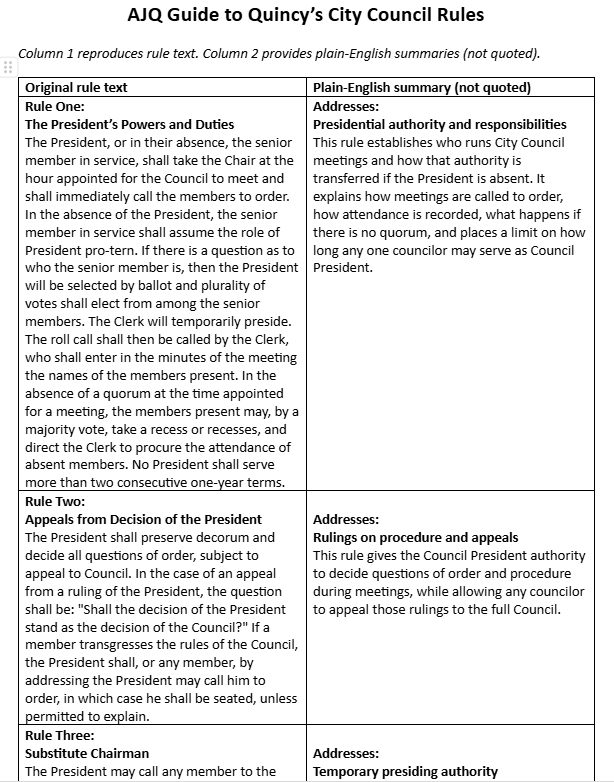

AJQ’s Guide to City Council Rules

I made an explainer on the City Council rules. Click on the orange button above or the preview image below to see the document.